While some proton therapy centers across the country have reportedly struggled to stay profitable, officials at University Hospitals say they’ve found the “sweet spot” two years after the Cleveland-based health system opened its own $30 million center.

UH’s Proton Therapy Center, which saw its first patient in July 2016 and is the only of its kind in the region, serves at least 20 patients a day, which puts the center in a financially healthy position to sustain its $25 million annual budget, said Dr. Ted Teknos, president and scientific director of UH Seidman Cancer Center.

“I think we’ve had great success with the proton therapy center here at University Hospitals,” Teknos said. “We’ve set goals, which were relatively modest to begin with, but have certainly increased over time. And we’ve been able to certainly achieve what I’d like to say essentially continued growth in the use of our proton therapy machine servicing the people primarily of Northeast Ohio.”

Proton therapy is a form of radiation treatment with unique properties that target a tumor while reducing the effects on surrounding healthy tissue. The therapy has clear indications for treating certain tumors, such as pediatric brain tumors, skull-based tumors and head/neck cancers, Teknos said. Reducing the effects on surrounding healthy tissue is especially important in children and in cancers near vital organs like the heart and brain.

There are 28 operating proton therapy centers in the United States, said Scott Warwick, executive director of the National Association for Proton Therapy, a nonprofit trade group that works to educate payers, physicians, patients and policy makers on the clinical benefits of proton therapy.

The association began in 1990, founded in collaboration with the opening of the first proton therapy center in the United States at Loma Linda University Medical Center in California, Warwick said. The next opened in 2001, and the field has “grown what we consider responsibly” with roughly one and a half new centers opening annually since then.

What was initially a destination medical treatment has become a regional service line offering. Only about 7% of UH’s proton therapy patients come from outside of Ohio. UH was the first to open a center in Ohio, with University of Cincinnati Medical Center and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center partnering shortly after to open the second in the state.

Cleveland’s other large health system, the Cleveland Clinic, has no plans to obtain proton therapy technology, said Dr. John Suh, chairman of the Department of Radiation Oncology at the Clinic’s Taussig Cancer Center.

“The reason we have not actively pursued proton beam therapy is that the number of indications and the evidence for the use of proton beam therapy is still lacking,” he said.

Although Suh believes the technology could benefit some specific populations of patients, especially younger patients, he said there are not enough clinical studies at this time proving the superiority of proton therapy for the Clinic to invest in it.

The New York Times recently reported that while most of the proton centers in the United States are profitable, the industry is “littered with financial failure.” The Times reported that nearly a third of the existing centers lose money, have defaulted on debt or have had to overhaul their finances.

Warwick said that estimate “sounds high” to him, but he recognizes that some centers have struggled. They face the same issues any business would, including a large debt load. Before relatively smaller systems like the one in Cleveland came online, the average cost for a center was between $100 million and $150 million.

“We’ve now entered a phase in the industry where small centers like the one at University Hospitals — small one-room centers — have drastically brought down the cost to provide proton therapy,” Warwick said. “Those centers who have lower cost structures or significant philanthropic efforts do well.”

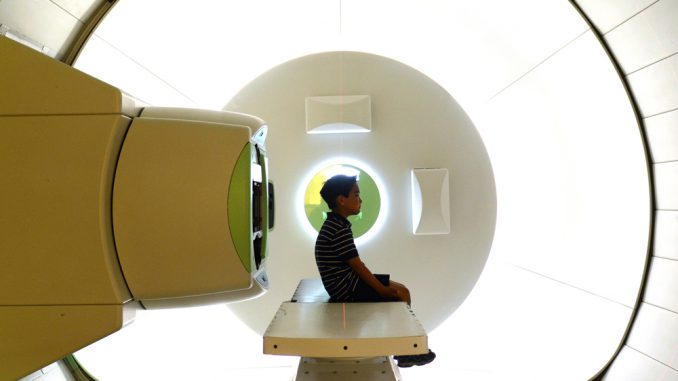

Behind a wall in UH’s Proton Therapy Center, a 20-ton cyclotron supported by two gantry arms rotates a machine 180 degrees around a patient — one floor below and above an unassuming treatment room. It’s considered the compact version of the technology, which can take up an entire city block in other models. UH has just one treatment room, compared to other centers, which hold a few.

“To be fiscally prudent, we opted for a smaller investment with a single treatment area that really comes at a fraction of the cost of the larger centers,” Teknos said. “So from that perspective, we’re very good stewards of our resources to opt very early for the single chamber system, which wasn’t as large of a capital outlay in the beginning.”

Thus far, UH has been able to stay budget neutral on its Proton Therapy Center. UH calculated the number of patients needed to break even and budgeted to average just under 18 a day this year. Since April, they’ve averaged 25 a day.

UH has had a “fair amount of success” getting the treatment approved by payers, and that’s improved over the two years the center has been open, said Brenda Myers, director of radiation oncology and UH Seidman Cancer Center support services. Through a deliberate effort, they’ve been able to get things approved that two years ago would have just been a “no,” Myers said.

“We’re not trying to just push volume; we’re trying to push the most appropriate patients to achieve the state of the art therapy that’s appropriate for their diseases,” Teknos said. “And I think insurance companies have realized that we only go to them with legitimate indications for proton therapy.”

Working with insurance companies has proved to be a challenge for many proton therapy centers. Warwick said the National Association for Proton Therapy is actively working to hold “insurance companies accountable in their review of the clinical evidence.” He argues that if the industry didn’t face “inappropriate denials of treatment” by commercial insurers, no centers would be struggling.

“Over the last three years, over 285 clinical papers have been published, and the large majority of those continue to demonstrate the clinical advantages of proton therapy,” Warwick said.

UH is working on some studies of its own, specifically in esophageal cancer and prostate cancer.

“We want to treat the patients where there’s ample evidence that proton therapy is better than conventional radiation therapy,” Teknos said.